More Than Just Metal: Training the Next Generation at Sam James Engraving

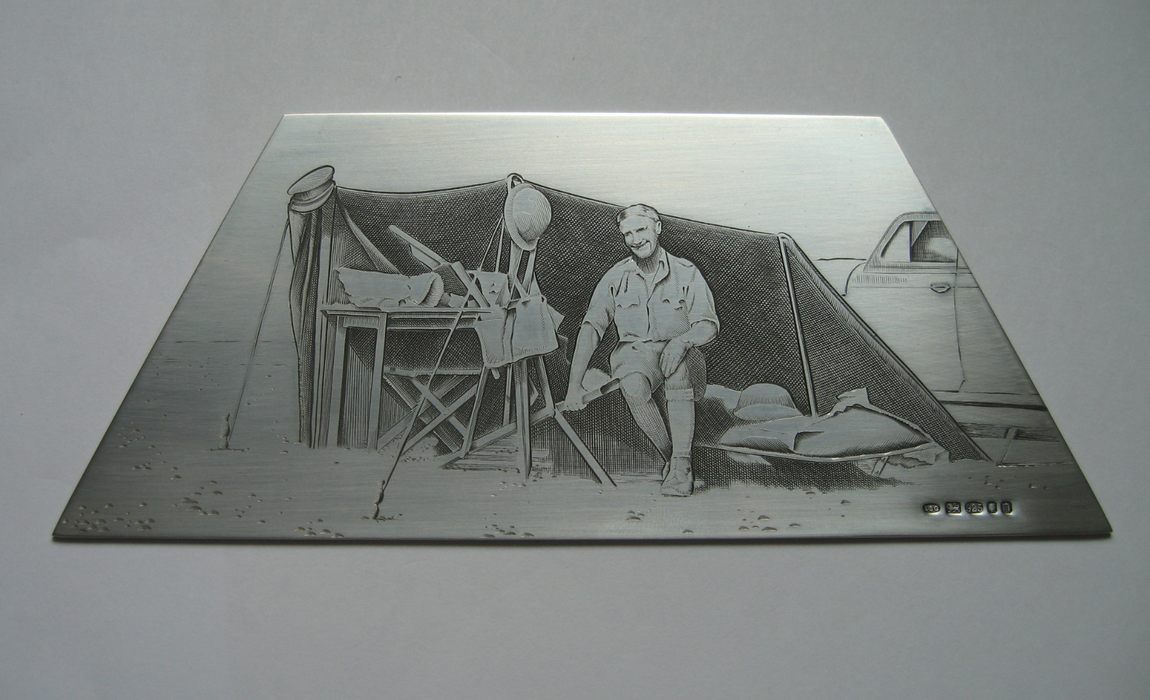

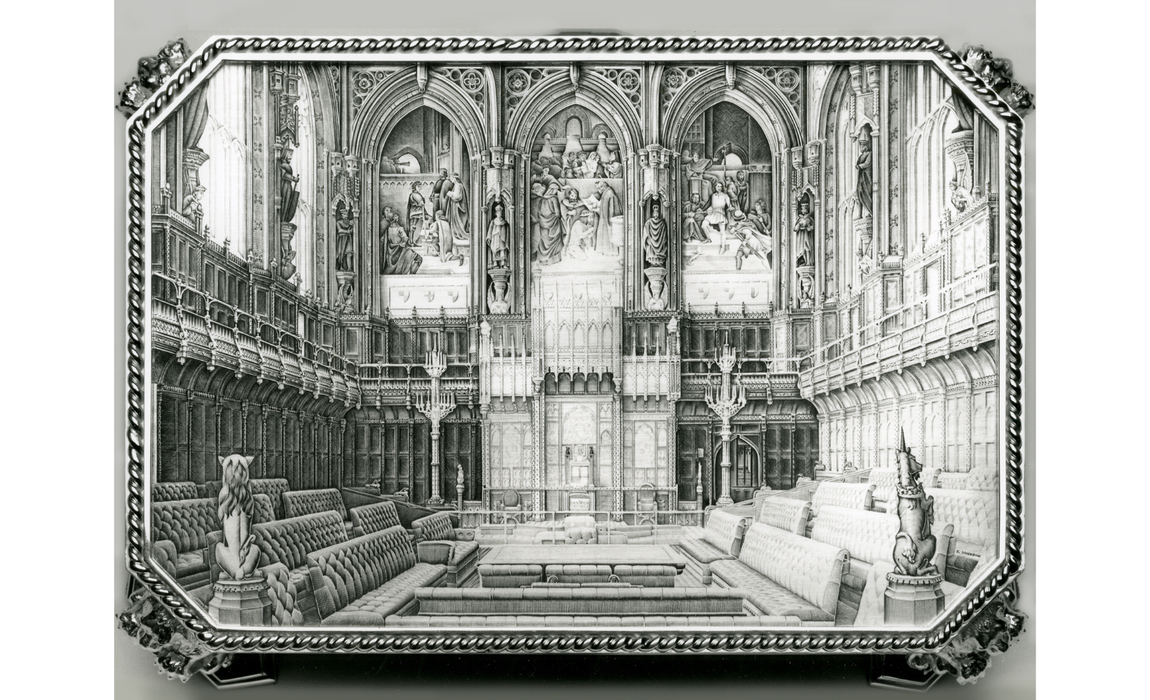

In a quiet workshop, James Neville guides his graver across a silver surface – each line the result of decades of skill, patience and precision. Hand engraving is one of the great traditional skills of the jewellery and silversmithing world. Yet it’s also increasingly rare, now listed as endangered by the Heritage Crafts Association, with concerns about its long-term survival.

At Sam James Engraving Ltd, James and his business partner, Samantha Marsden, are working to change that. With over 40 years in the trade between them, their studio at the Goldsmiths’ Centre is one where a team of hand engravers work side-by-side – not just preserving traditional skills, but actively passing them on to the next generation. By nurturing apprentices and welcoming the public through their doors, the studio is helping to rewrite the future of this overlooked craft. In this interview, James reflects on his own journey, the evolving identity of the engraver, and the importance of passing these techniques to the next generation.

Origins in Engraving

I studied BA Visual Arts, specialising in Silversmithing and Metalwork, at Camberwell College. Very early on during the course, I tried my hand at engraving and really liked it, but no one at Camberwell could properly teach me. So I began looking externally for training opportunities. Eventually, I found a workshop that was affiliated with the Goldsmiths’ Company with a strong tradition of training. Through that workshop, I secured a trainee position and became an engraver quite quickly.

I worked with that company for about ten years. After that, I left and worked independently for around a year. Then I began discussing a business partnership with Samantha Marsden, who already knew about the Goldsmiths’ Centre – which was in its infancy at the time. She had been approached as an award-winning engraver to apply for a workshop there – she’d won a Cartier Award from the Goldsmiths’ Craft & Design Council – and we decided to set up a business together.

“The timing couldn’t have been better. From the outset in 2012, there was this real mix - some of the businesses were new like ours, others were well established, and some were staffed by just one person. It felt like a very safe, vibrant environment to start a business in - somewhere I didn’t mind taking the plunge. People helped each other set up their spaces, you’d knock on someone’s door to say hello or get advice - there was a real sense of camaraderie. I would be a lonely soul working in a shed if it weren’t for the community at the Goldsmiths’ Centre.”

Finding a Gap in the Industry

Aside from the immediate support and community, we found that just being physically based in the Goldsmiths’ Centre helped us grow. The kind of foot traffic that comes through – clients, other craftspeople, industry figures – it’s a real hub. We got new customers through word of mouth, recommendations from people within the building, and from visitors who just wandered in. It helps spread awareness of engraving, which is a dying art, and creates opportunities that we never could have predicted. It also helped us identify a big gap in the trade: you just don’t find many engravers nowadays.

The ones who are still working are often older, working alone, or already settled in their routines. So we realised we were in a unique position: we had a team of seven or eight hand engravers, all working under one roof. That’s almost unheard of. Usually you might find a duo – a machine engraver working alongside a hand engraver – but not a whole workshop of hand engravers doing such a wide variety of work.

That diversity really set us apart, and as our workload increased, we decided to take on apprentices. It was literally a case of walking across the courtyard and knocking on a door at the Centre to ask how we could get an apprentice – and they sorted it out. Since then, we’ve always had one. We’re now on our fourth apprentice.

Training the Next Generation of Engravers

People often ask, “Why not use a laser?” And while we do use machines where appropriate, it’s not the same. Hand engraving offers a depth and artistry that technology can’t replicate. We try to strike a balance between embracing the use of technology and preserving traditional craft.

Training apprentices has been a real privilege. You invest so much time in training them, but we’ve been lucky – all of ours have stayed. Jack, our first apprentice, was with us for twelve years, Lou ten, and Celeste recently completed her apprenticeship and now works with us as a professional engraver. Watching them grow has been incredibly rewarding.

They’ve become skilled and confident professionals in their own right – contributing ideas, supporting one another, and helping the studio evolve. This two-way exchange is something we’ve always encouraged. Engraving can be solitary, but here there’s real community. Whether it’s conversations with students or visitors on tours, there’s always engagement – and sometimes, new commissions come from it.

We approach training realistically. Not every apprentice wants to be an artist or independent maker – some simply want to do the job well, and that’s just as valuable. The apprenticeship system has come a long way too. When I started, there were no formal qualifications. Now, apprentices finish with the equivalent of a second-year degree, giving them options and security.

The Centre’s setup helps enormously. Our current apprentice, Isabel, does Day Release training – learning, working, and studying all in the same building, all without disruption or extra commuting. It makes learning a craft like engraving far more accessible.

Changing Demands in the Trade

The expectations around what it means to be a craftsperson have changed. Not every apprentice wants to become a designer or a public-facing maker, and that’s something the industry is only just starting to acknowledge.

“Some engravers simply want to master the technical side of the job, execute work to a high standard, and operate as part of a production team rather than fronting their own brand. That kind of skill is no less valuable.”

We’ve trained apprentices who are artists in their own right, but we’ve also supported people who take satisfaction in doing reliable, consistent work that meets a client’s brief exactly. The training structure didn’t always support those different paths – but it’s improved. The newer system offers formal qualifications and gives young craftspeople more flexibility if they decide to shift direction later.

Giving Back to the Community Through Teaching

Both Samantha and I have taught at the Centre – running workshops, offering introductory engraving sessions, and supporting students with engraving projects as part of their coursework. It’s been a real pleasure to be involved in that way. Teaching not only allows us to share what we know, but also deepens our own understanding of the craft. It connects us with other disciplines and generations, and opens the door to new conversations.

Some of the postgraduates we’ve worked with have even gone on to receive QEST (Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust) funding to train with us, and being in the same building makes it easy to stay in touch. Our aim was never to turn students into engravers, but to show them how engraving can be integrated into their own practice, even if they never pick up a graver again. We wanted to expand their thinking: to show that engraving isn’t just about pictures or lettering. It’s a practical tool. For example, gravers can be used for filing, cleaning up, or finishing work in ways many hadn’t considered.

A lot of students would say, “I didn’t realise I could use it like that.” That’s the goal – to give them just enough knowledge to make engraving immediately useful. Even learning how to sharpen a graver can improve their work straight away. Louise, our former apprentice, has even returned to do some teaching herself.

They keep inviting me back, probably because I’m honest about the realities of the trade. At the start of their course, students hear from a range of craftspeople, and it’s important that they get a realistic picture. It’s not all champagne, sales, and drawing pretty pictures. Engraving is a service trade, with many paths – from silversmith engraving to picture engraving, letter cutting, even the gun trade. That variety is part of what makes it so interesting.

The Importance of Connection in the Craft

We enjoy the variety involved in our work, even the so-called bread-and-butter jobs. Those basic, repetitive tasks are often just as satisfying. The problem is, people sometimes forget that. They see the glamour pieces – big commissions that only come once or twice a year – and think that’s all there is. But the reality of craft and running a workshop is much more complex.

Even with marketing, there’s this idea that you make something beautiful, people fall in love with it, and you sell it. But it’s hard. It’s difficult to finance, to elevate your practice, to keep going when things aren’t selling. That’s why the training and talks we give – whether in person or now online through programmes like Getting Started Online – focus on the reality: this is what our workshop looks like, this is what we do, and here’s how we actually make it work.

Not every engraver wants to be an artist. Some just want to do a job well. There’s real value in being able to deliver exactly what’s required with skill and precision.

Keeping the Craft Viable

“One of the biggest challenges we face now is showing people why hand engraving still matters. From the outside, it’s easy to assume everything can be done by machine or laser – and yes, those technologies exist, and we use them ourselves where appropriate.”

There’s a depth, sharpness and quality to hand engraving that can’t be replicated by automation. It’s slower, yes – but also more intentional.

The problem is that not everyone sees that value straight away. Clients often expect speed and low cost – not because they’re unwilling, but because they don’t understand what goes into this work. We’ve had to learn how to explain it, to educate as we go. That’s part of why the visibility that comes with teaching and open-door events matters so much. It helps us advocate for the craft itself.

The key is balance: using new tools without losing sight of the tradition, staying commercially viable without compromising standards. The more we can be honest about what this work involves – and the more we can bring others into that conversation – the better the chances are that hand engraving will have a future. As more traditional engravers approach retirement, the gap in the trade is only widening. We’re doing what we can to make sure it doesn’t close entirely.